In the previous part of this article series, a general overview of concrete in construction was presented. To better understand the nature of concrete, let’s take a closer look at its life cycle.

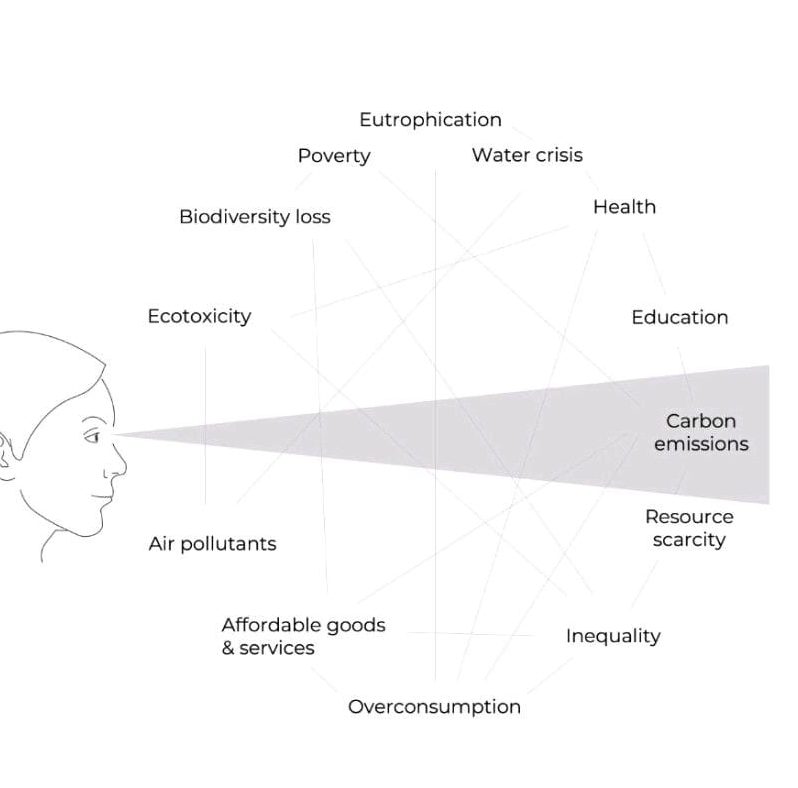

The first stage, material acquisition (A1), involves obtaining the necessary raw materials to produce the final product. Cement is a mixture consisting mainly of clinker, which is produced in the calcination process of calcium carbonate. In this case, calcination aims to obtain calcium oxide from limestone. However, during the heating process (roasting), carbon dioxide is also produced. According to the “CO2 and Energy Accounting and Reporting Standard for the Cement Industry” report issued by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in 2011, for every ton of calcium oxide produced, 785kg of carbon dioxide is emitted.

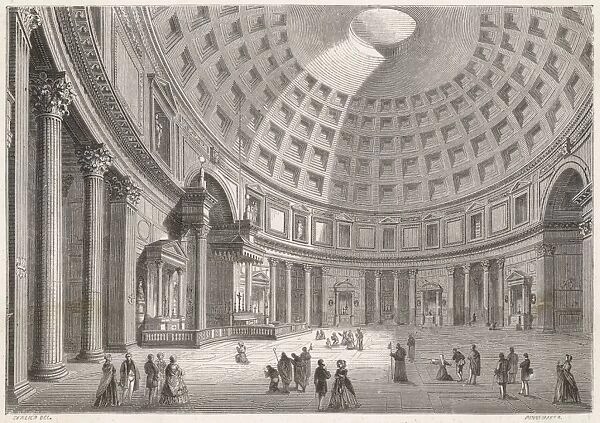

1 ton of calcium oxide = 785kg of carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a by-product of the chemical process; changing the energy source needed to heat the limestone to renewable energy will reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted in the cement production process, but it will not eliminate it. Clinker cement will always be responsible for carbon dioxide emissions. As mentioned Part 1, in vernacular architecture, different binders were used: volcanic ash or plant extracts. Pozzolana, a type of siliceous volcanic ash, which, when mixed with lime and water, creates a waterproof, hydraulic binder. Its name comes from the city of Pozzuoli in Campania, near Naples, where there are rich deposits of the highest quality raw material. Pozzolana was well known in ancient times and described by Vitruvius in “De Architectura”:

There is also a kind of powder which from natural causes produces astonishing results. It is found in the neighbourhood of Baiae and in the country belonging to the towns round about Mt. Vesuvius. This substance, when mixed with lime and rubble, not only lends strength to buildings of other kinds, but even when piers of it are constructed in the sea, they set hard under water. The reason for this seems to be that the soil on the slopes of the mountains in these neighbourhoods is hot and full of hot springs. This would not be so unless the mountains had beneath them huge fires of burning sulphur or alum or asphalt. So, the fire and the heat of the flames, coming up hot from far within through the fissures, make the soil there light, and the tufa found there is spongy and free from moisture. Hence, when the three substances, all formed on a similar principle by the force of fire, are mixed together, the water suddenly taken in makes them cohere, and the moisture quickly hardens them so that they set into a mass which neither the waves nor the force of the water can dissolve.

(Mary Evans Picture Library)

Bernard Rudofsky also conducted research on concrete architecture. In his doctoral thesis, “Eine primitive Betonbauweise auf den Kykladen” he focuses on the concrete architecture of the Cyclades. He points out, among other things, the relationship between the material resulting from volcanic eruptions and the architecture of the island of Santorini. His research during his doctorate laid the groundwork for the exhibition “Architecture without Architects” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1964 and the publication which reminded the international discussion of the role and diversity of architecture, materials, and territory.

If we look at the vernacular architecture of different regions, we can observe the diverse use of concrete and concrete-like materials. In ancient Mayan construction, resin extracted from endemic plants of Central America was used as a binder for mortar: chukum and jiote. When immersed in water, the bark of trees secretes a material with a high content of polysaccharides, which have binding properties. Resin, when mixed with lime, sand, and water, creates a durable mixture. Research by Carlos Rodriguez Navarro of the University of Granada indicates that cement produced in this way has similar properties to lime cement and dissolves more slowly than inorganic mortars in tropical climates. Cement produced based on organic material does not undergo the calcination process and does not release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. An article published in 2023 reverberated loudly and opened another path for research into alternatives to cement.

Ancient concrete made from volcanic ash does not meet the stringent technical standards that modern industry imposes on materials. It seems difficult to achieve C20/25 concrete using heterogeneous materials that have not undergone industrial processes. Nevertheless, an international group of researchers in an article on Santheu concrete (made with rice and egg white as binders) writes that compressive strength tests have achieved even C50 concrete. Industrial processes took a different path at the beginning of the century, focusing on optimising clinker cement. The diversity of regional solutions known from traditional construction shows that alternative solutions do not emit carbon dioxide and could replace limestone cement. They definitely require further research. Today, pozzolana or fly ash are sometimes used in mixtures of some Portland cement. Ash is a by-product and waste product of the fossil fuel combustion process. It contains small amounts of toxic beryllium and easily soluble sulphates that can seep into the groundwater system and pollute it.

In addition to cement, concrete consists of aggregates and water. As Bjorn Berge points out in “The Ecology of Building Materials”, mainly sand, slag, and crushed stone are used as aggregates. In locations where these materials are not available, construction waste is also used, provided it does not cause undesirable reactions with the cement. To calculate the impact in the A1 process, we need to analyse the environmental costs of extracting sand and crushed stone. The “Life Cycle Assessment of Aggregates” report indicates that the biggest burden is the loading process reflected in carbon dioxide emissions, which occur during the combustion of fuel powering the machines. In the case of sand extracted from land and rivers, the Acidification (land and freshwater) index stands out negatively among the others. If we consider the EPD of prefabricated concrete columns produced by INUS in Lithuania, we can see that in stage A1, about 93% of carbon dioxide is produced in the cradle-to-gate cycle or about 90% in the cradle-to-grave cycle. Similarly, in terms of ODP, Acidification, Eutrophication of land and water, raw material, and energy consumption. Stage A2, the transport of raw materials, accounts for less than 0.1% of the total life cycle.

The next stage, material production (A3), includes all industrial processes related to the production of concrete or concrete elements (columns, slabs, etc.). A typical concrete mixing plant consists of a mixer, where cement, aggregates, water, and additives are weighed and mixed in strictly defined proportions to produce concrete with specified technical properties. Aggregates of various particle sizes (gravel, fine gravel, sand) are stored in separate piles. The loader fills the aggregate bins, from which the required amount is taken and transferred by conveyor belt to the mixer. Cement is stored in separate silos depending on its quality and added to the mixer using conveyors, water, and additives using pumps. After the required mixing time, the fresh concrete is loaded onto a concrete mixer and delivered to the construction site. In this stage, mainly energy and fossil fuels necessary for the operation of machines are consumed. As various Environmental Product Declarations show, this process primarily contributes to the production of greenhouse gases for the phase. At this point, we close the cradle-to-gate cycle. The product is ready. Most often, the manufacturer takes responsibility and calculates the environmental impact only up to this stage.

Stage A4 involves transporting materials or components from the factory to the construction site. Similarly to stage A2, the associated impact is related to the means of transport and represents a marginal part of the impact. I often encounter surprise from designers for whom the construction site is associated with the highest costs. It is likely to be the longest stage and requires the highest investment for architecture and architects. However, from both LCA and LCC (Life Cycle Cost) perspectives, which account for the building’s whole life, we should consider it a small part of the process.

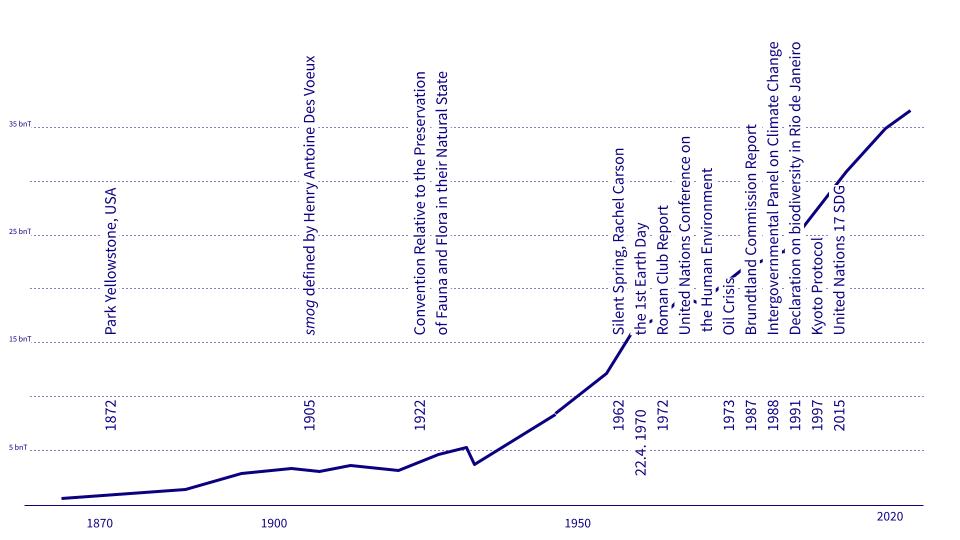

Summarising stage A, the biggest negative impact is associated with the emission of greenhouse gases and occurs during calcination. Other indicators that negatively affect the environment are caused by transportation and are observed in eutrophication processes, acidification, and summer smog (POCP).